Witches to Feminists: how women are still burnt at the stake

What the history of the witch hunts can teach us on the scapegoating of women and feminism

Any woman can be a witch. A term that has been emptied of its historical meaning to become a parody, yet, it sometimes resurges, spat as an insult to women straying from the strict feminine gender norm, women too powerful and endangering the status quo. How we perceive women today is still widely influenced by the propaganda employed during the witch hunts. The sequels on society have persisted through the centuries, a wound that never healed and left a scar we keep picking at through misogyny, sexism and the perpetuation of gender roles. Behaviours that were susceptible to having women arrested for sorcery are still ingrained in gendered cultural behaviour and viewed negatively by society; for example, a woman’s reputation could have cost her her life in the 1600s1 and it has remained an essential component of girls’ education.

Witches never left our collective imagination and have been moulded into fantasies. From fairy tales and movies to TV series and books, witches are portrayed as young enchanting temptresses or old vengeful and wise hags. The reality of contemporary witches, who follow various pagan traditions and ancient religions, does not have much to do with fictional representations of supernatural witches like the Halliwell sisters in Charmed. Vilainised through a picture: a wrinkled, hooked nose woman, living on her own and who would sacrifice children for vanity.

Witches perpetuate a plethora of clichés, an unconscious reminder of forgotten transgenerational trauma, now ridiculed.2 After all, the witch hunts were some 400 years ago.3 Weren’t they?

The history of witches and witchcraft is ancient and hard to trace, evidence can be found as far back as ancient Mesopotamia. Rituals and practices transcend times and places, for example, the ancient Greek goddess of sorcery and necromancy, Hecate, is still worshipped in modern rites. Elements of Native American, Caribbean, Asian and African rituals are used across the world, by ancestors but also through cultural appropriation, a reminder that the history of the witch hunts is tightly connected with the history of colonialism. Records of witches’ beliefs are so widespread through civilisations “It’s more difficult to prove that no one practises ‘witchcraft’, that is, conducts rites or utters curses in an attempt to harm others.” writes Gregory Forth, in aeon. For many historians and anthropologists like him, a witch corresponds to what he describes as someone who ‘uses malice, wilfully harms other people by unseen, mystical means’.

For the purpose of this article, I prefer the definition given by Silvia Federici in her analysis of the witch hunts: the incarnation of a world of feminine subjects capitalism must destroy, listing the heretic, the unsubdued woman, the healer, the woman who dares to live alone, the one inciting revolt.4 The essence of which still lives, as I said, any woman can become a witch.

The idea that witches were followers of the devil was reinforced by the Malleus Maleficarum, a book published in 1487 by the catholic inquisitor Heinrich Kramer.5 Previous to that, witches, ‘bad’ and ‘good’, were accepted as part of the folklore and held a role in the community. The Malleus propagated the belief of an imminent threat posed by witches. Used by all the judges and demonologists during the trials, the medieval ‘bestseller’ described in great detail how to find and prosecute witches.6 Using the Church dogma on heresy to harden folklore about witchcraft, the Malleus is at the roots of the misogyny behind the hunts as it argued women were more prominent witches than men. Tactics similar to the ones used to villainise feminists today.

In her brilliant article How the Printing Press Ignited Europe’s Deadly Witch-Hunt Frenzy,

draws a parallel between the use of the then-new technology, the printing press, and today’s use of the Internet:The history of witch trials clearly shows us what happens when technology-fueled misogynistic propaganda gets out of control. It can terrorise entire societies, isolate its victims, discourage resistance, and make people follow along because ‘everyone else is doing it.’ And it doesn’t just lead to social polarisation, but to violence. We might not be burning women at stake anymore, but the rates of gender-based intimate partner violence, sexual violence and online harassment remain staggering.

The violence of the witch hunts and trials has merely muted into more symbolic forms of violence through sexism, misogyny, financial inequity, oppression to fit narrow gender standards… Fear has been widely used for centuries to subdue rebellious women and girls: by not subscribing to a certain type of femininity standards women are at ‘risk’ of being outcasts, undesirable.

Varying in intensity, from forced pregnancies (USA) to the attempted annihilation of women from society through their removal from the public space (Afghanistan under the Taliban), violence remains a tool to control women and force them into the domestic sphere. It is also worth noting that women are still being tried for witchcraft in certain regions. India’s case is well-documented, or notably in Saudi Arabia, where witchcraft is punishable by beheading, an ‘anti-witchcraft police unit’ that deals with the many claims (often made against immigrant domestic workers because of foreign practices and beliefs).

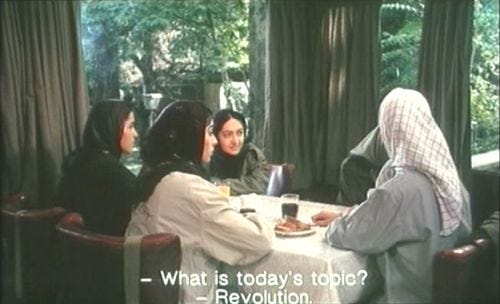

Women have always been at the forefront of revolutions and movements are more likely to succeed when women are involved, which is why it is so important to authoritarians to control them as tightly as possible.7 In a 2022 Foreign Affairs article, Erica Chenoweth and Zoe Marks explain that it is not a coincidence that women’s equality thins out as authoritarianism rises, “Political scientists have long noted that women’s civil rights and democracy go hand in hand, but they have been slower to recognize that the former is a precondition to the latter”. Therefore, being sexist and preaching against women and women’s rights is to the advantage of those who want to seize power.

As mentioned in The medieval revival, the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance was marked by transitions: from feudalism to capitalism, the Church Reformation and a new form of governance. It was also the end of magic and commons in favour of individualism and rationalism. It was a time of deep societal change that forged society into what we still know today. The witch hunts, aided by emerging capitalism and a demographic decline, transformed women into domesticated wombs.

15th Century witches were not revolutionary feminists, most of the time they were vulnerable: women living alone or immigrants, older knowledgeable women who were a threat to the new power, widows, or simply women who were a burden to somebody else (jealousy, adultery, all were valuable reasons to send someone to the stake). Women, nonetheless, were already a threat, often being the first ones to rise against the governments to demand food when famines were ravaging northern Europe. As stated by Bianca Bosker in the Atlantic, “Throughout history, attempts to control women have masqueraded as crackdowns on witchcraft, and for some people, simply self-identifying as a witch—a symbol of strong female power, especially in the face of the violent, misogynistic backlash that can greet it—is a form of activism”.

According to Silvia Federici, it is the transition into capitalism and primitive accumulation that formalised the oppression of women, reducing them to a life of domesticity and the procreation of future workers. The transformation was systemised and enforced with the witch hunts, ‘the witch hunts in Europe were an attack against the resistance of women to the progression of capitalist relations, against the power they disposed of, thanks to their sexuality, and the control they had on reproduction and their skills to heal.’8 A situation reminiscent of today’s challenges…

Masked under concerns of demographic decline, capitalist elites are increasingly putting natality on the political agenda. Policies repeatedly oriented towards controlling women and their bodies instead of addressing other probable causes of low natality (cost of living, environmental concerns, housing crisis, widening ideological gap between men and women…). Even more alarmingly, the right, aided by the manosphere, is scapegoating women and especially feminists as the cause of all evil that is happening to men. The traditional gender role they promote is nothing but an attempt to reinforce the patriarchy and force women back into the house to perform free productive labour, subjugated to a man. And those who revolt can expect the worst.

Post Scriptum: I could have continued writing on the topic for pages but I need to stop and keep some of it for other articles (coming soon, i promise).

As always, thank you so much for reading. If you can share or like or comment it would mean the world to me, if you haven’t already subscribed and wish to receive my future posts:

/sources + resources/

How does trauma spill from one generation to the next?, The Washington Post

Transgenerational trauma – violence shapes us, Medica Mondiale

Why Witchcraft Is on the Rise, The Atlantic

From Circe to Clinton: why powerful women are cast as witches, The Guardian

How to be a witch without stealing other people's cultures, Mashable

Revenge of the Patriarchs, Foreign Affairs

Caliban et la Sorcière, p.296, Silvia Federici, Entremonde (all quotes are freely translated from French).

Caliban et la Sorcière, p.328

The last witch execution in Europe took place in the late 1700s.

Caliban et la Sorcière, p.19

Publication date varies between 1478, 1486, 1487…

Actually a bestseller, it was re-edited 28 times between 1486 and 1600 and was accepted by both Catholics and Protestants.

This will be an article on its own, I have too many things to say - especially about Iran, Iranian women are lions.

Caliban et la Sorcière, p.272