Joan of Arc, feminism and the aesthetics of a martyr

what made her an icon for everyone, from fascist to feminist?

This article started as one reflection on a medieval revival and the aesthetics around it and it quickly took over my whole brain. In this three-part analysis, we’ll explore the links between the witch hunts, feminism and the roots of capitalism. I loved writing and researching these topics and I hope you will enjoy reading it.

My interest was sparked by the cultural revival of medieval aesthetics and iconography over the last few years. TV shows; from Game of Thrones and its prequel, Vikings, the Tudors and others; the ever-growing popularity of romantasy. On the catwalks, chainmail and capes are in and out every other season, often mixed with silk, leather, corsetry, or even armours - COS even offers a chainmail tie. Even further, some people swear by herbal remedies, rituals from a previous time and a wider ‘return to nature’.1

But one icon stands out. What really grabbed my attention was the aesthetisation of Joan of Arc. Two recent cases to be precise: Zendaya climbing the 2018 Met Gala stairs in a custom Versace chainmail dress, and Chappell Roan’s performance at the VMAs in armour (and her red carpet moment putting paparazzi back in their place). On Pinterest the research Joan of Arc swarms with modern interpretations of the martyr, and Etsy ads for made-on-measure chainmail fauconière (which may or may not be on my wishlist), metallic gloves, and other related items.

Well before that, Joan of Arc has been a source of inspiration for decades; artists, fascists, feminists, all find something in the Maid of Orléans. But what made her such an icon for everyone from fascist to feminist?

First, a quick recapitulation of the lore.

Joan of Arc is mostly known for her central role as the virgin saviour of catholicism and France, the leader in shining armour of troops who lifted the Siege at the Battle of Orléans in 1429. The English captured and executed her two years later. Accused of heresy, dressing as a man and witchcraft, Charles VII, who she helped being crowned, did nothing to save her from death.

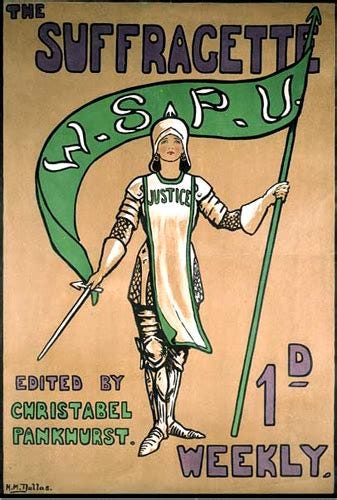

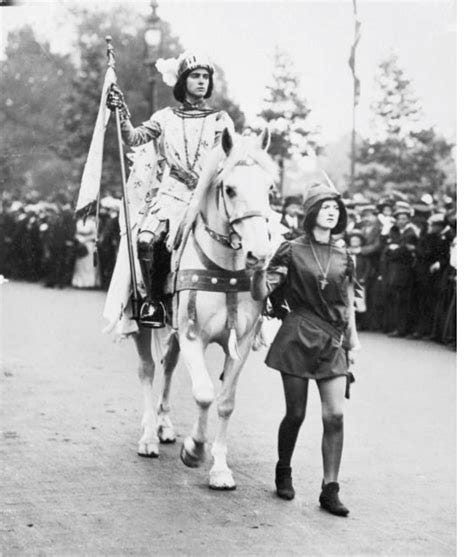

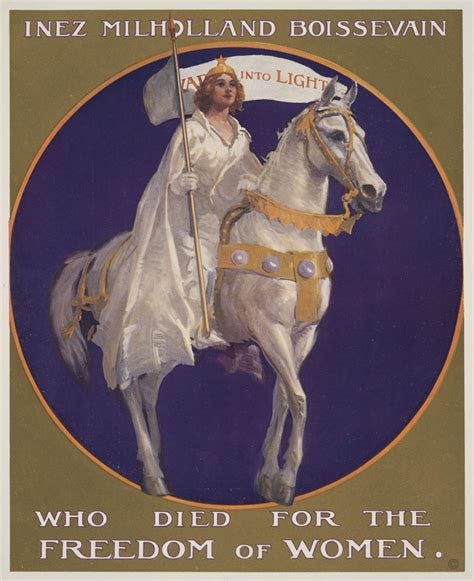

A virtuous patriot, chaste and martyr, are the central elements to the Church and nationalists. A soldier, heroin in the time of heroes, defier of men when her father tried to marry her, made her an icon for early feminists. A woman celebrated before being burnt at the stake.2

How can the same woman be branded as a heretic in 1431 and canonized as a Saint in 1905? This has been a question scholars have debated for centuries (…)

I could not help but smirk when I read this sentence on the Library of Congress dedicated page. Were all those scholars men? As if rampant misogyny wasn’t something in the mid-15th.

In France, her status has been captured by nationalists as a symbol of resistance during invasions of foreign invasion (the Germans mainly), which in turn was taken by the far-right as a symbol of resistance against foreigners invasion (migrants and refugees, especially Muslims). She is associated with a certain vision of France, one that is pure, white and catholic, becoming a xenophobic symbol. When in Paris, it is the far-right who rallies at the foot of her gold status, in 1900s London, the suffragettes rallied at her foot for a different reason.

Rehabilitated by the suffragettes as a feminist in the early 1900s, Joan of Arc was an unlikely icon. After all, she was an ardent Christian and a strong believer in Church supremacy and the French Monarchy. It is unlikely she would have supported women’s right to vote, yet she broke all gender barriers when she claimed her place on the battlefield, cross-dressing as a man - a soldier, a knight.3 It is to be noted that, feminists of the late 19th and early 20th century were, for most, Catholics, and Joan of Arc offered the perfect combination of religious beliefs and militancy. Her rise as a feminist icon also comes within a wider rediscovery of the witch hunts through a feminist lens, although her execution, politically motivated, came a few decades before the witch trials.

Nowadays, I think it is the symbolism of a young woman being revered as a saint before being burnt at the altar of politics that resonates with feminists. The early revival made it easier to remove the Church from the icon, leaving only the ‘badass, androgynous heroin’. Everywhere but in France, where she stands as a nationalist (derogatory) idol.

Her image was exploited, her story was reinterpreted times and times again, myriad of symbolics were attributed to her - a teenager, her name used and abused across history. Ultimately, she is a woman in the public eye even centuries after her death, her fate follows the same as many other women after her. Sacrificed for politics, condemned for heresy, a vessel made empty to be refilled with our fantasy of who she could have been.

/sources + resources/

Caliban et la Sorcière, Silvia Federici, Entremonde (French edition)

Joan of Arc - feminist icon?, The Guardian

How Joan of Arc Inspired Women’s Suffragists, The Public Medievalist

This is part of a whole other topic, from the return of paganism and witchcraft to the spirituality to far-right pipeline (aka conspirituality, which I mentioned here).

Here lies the central element for artists, women especially. See “being woman’d”.

I stand by the cross-dressing, by definition “a person who wears clothes typical of the other gender”. This is what it was in the 1400s.